At Mello Workshop 2015 I presented a workshop on the topic of how a private investor might construct a high-yield portfolio, with moderate effort, and covered the many mistakes that I've personally made while following this strategy.

Introduction

Mello Workshop 2015 is the latest venture from Mello Events and at the two-day event I ran a workshop on how to construct a high-yield portfolio. This seminar focused on the strengths and weaknesses of this investment method, a simple rules-based approach, and the historical performance of two real-money examples.

Presentation

There are many different ways to make money in the stock market and all of them are equally valid so long as they lead to a positive result. However the majority of these approaches are concerned with capital gains; when dividends are considered then this is usually as an hors d'oeuvre rather than the main course. So if you want to generate an income from your capital, as a pension replacement perhaps, then the options are more limited. For most people the 'done thing' is to purchase an annuity and swap the benefit of retaining capital for the certainty of an income for life. Fortunately there is an alternative...

Before I launch into the nuts and bolts of this presentation I'd just like to acknowledge the huge debt that I owe Stephen Bland. He began writing about his high-yield portfolio (HYP) approach on The Motley Fool website back in 2000 and has continued writing about it on the Stockopedia website and elsewhere. In more recent times he's launched his own newsletter, The Dividend Letter, where high-yield portfolios are created on a rolling basis. While this is a subscription publication the details of his strategy, which have barely changed in fifteen years, are freely and publicly available; it these details that I will talk about today.

So what is a HYP good for? Fundamentally it's designed to generate a reliable income that should, in the long run, keep pace with inflation. There will be ups and downs in this income (since there's no fund manager to 'smooth' underlying volatility) but on the whole it should naturally increase - unlike the interest from a savings account. That said the aim is to minimise this volatility, which stems from investing directly in equities, by acknowledging that risk exists and creating a portfolio that is resilient to unexpected events. A bonus of investing directly, rather than buying an annuity, is that all of the capital remains under your control; there are no irrevocable decisions to be made here and if you choose to spend your capital on a cruise then this option is always available.

Which brings me nicely onto the next benefit; this is (compared to most trading strategies) a very low-effort strategy. Shares are held for very long periods, if not for eternity, and the majority of trading decisions are driven by corporate events rather then an intrinsic pressure to make changes. As a result trading costs are very low and while this is a minor advantage there's no doubt that over a period of several decades the impact of even small fees can be a significant fiscal drag on returns.

Obviously a HYP isn't for everyone and they don't suit every temperament. If you like to react to current news, time the market or actively manage your shares in some other way then this isn't the strategy for you; a HYP is all about indolence and ignoring the chatter. The reason that income investors can afford to remain so hands-off is that this type of portfolio isn't fixated on capital gains; share values rise and fall constantly but this is irrelevant so long as the company pays out a dividend. Since these are only announced twice a year (or quarterly) then share price changes between these announcements are, arguably, of no interest. In fact if you're planning to hold your portfolio of shares for the very long-term then capital values are simply a distraction; far better to ignore news, beyond that related to dividends, and enjoy the regular payments into your bank account.

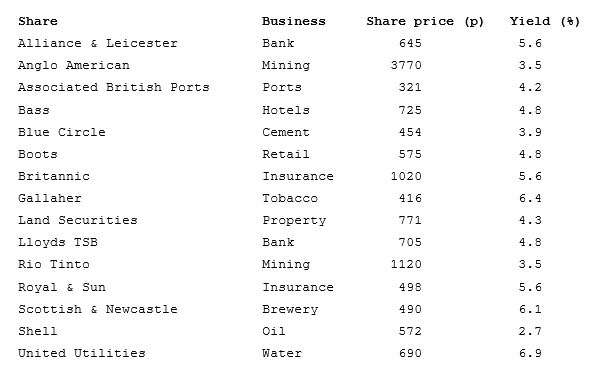

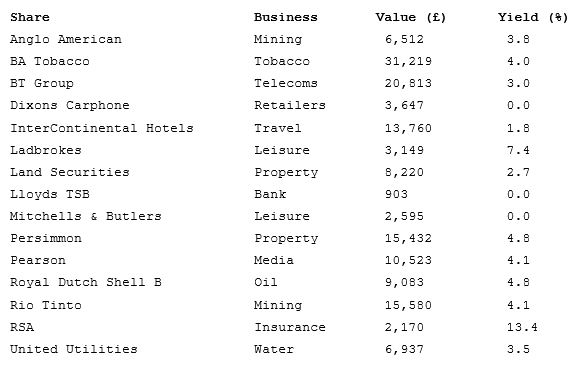

A problem with any investment strategy is that, a priori, it's impossible to know whether it'll work in practice. Even if someone has successfully followed this strategy in the past, or they've performed extensive back-testing and/or Monte Carlo simulations, it's still a big unknown as to what it may or may not do for you. For this reason Stephen Bland selected a real world portfolio (known as HYP1), based on his rules, back in 2000 and has reported on it annually ever since:

The idea here was to create exactly the sort of portfolio that anyone with a reasonable lump-sum, such as £75,000, might purchase and to track it over the years with as little input as possible; so holdings are only changed when forced to by corporate actions and replacement shares are selected using the same criteria as applied to existing shares. Fourteen years later the composition of the portfolio has dramatically evolved but it's still fulfilling its aim of generating an income for life:

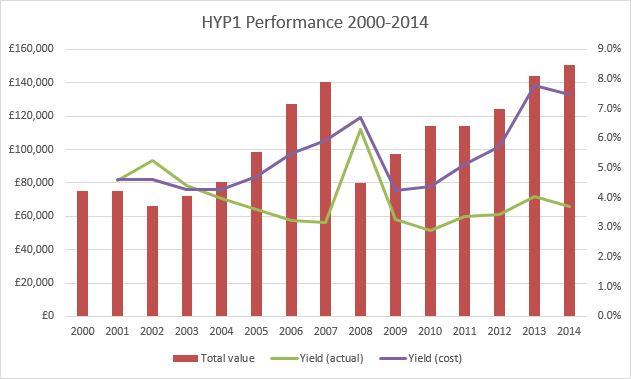

Looking at the performance of this 'one-hit' portfolio there are a few striking features. Most obviously the capital value of the whole has fluctuated dramatically over the years; after an early decline the shares put on a growth spurt and came close to doubling by 2007. With the benefit of hindsight we can see that this was a short-lived peak and overall it tumbled back almost to its initial value the next year. In time though the portfolio, if not individual companies, has recovered handsomely and is now sitting well above its previous high-water mark.

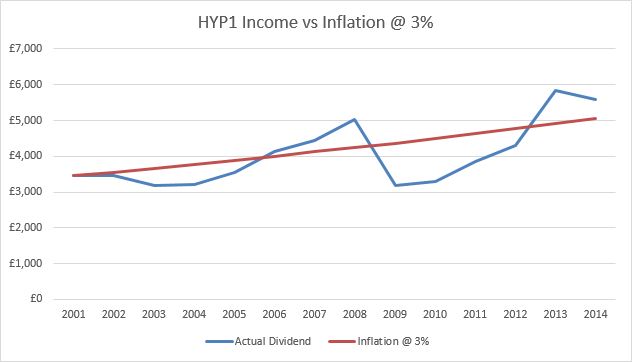

But that's not the point of a HYP - although if you don't have the stomach for such capital volatility then it's probably not a good fit for you - and instead it's the dividends that count. In the first year the total dividends came in at £3,451 (equivalent to a blended yield of 4.6%) and over time this value has fluctuated fairly dramatically (up to £5,040 in 2008 and down to a nadir of £3,187 in 2009). In the last couple of years though the portfolio bought in £5,828 and £5,601 as companies recovered along with the economy. So with income, as with capital, there's a capriciousness inherent in direct equity exposure which suggests that operating with buffer of a year or two's income would be extremely prudent.

A point worth noticing though is that, through thick and thin, the yield of the portfolio has remained very solid at around 4% (apart from an anomalous jump in 2008 as the capital value diminished even more rapidly than the income!). This compares very favourably with most other sources of income and suggests that even a non-tinkering portfolio can supply a decent and stable yield over time without actively chasing after the latest, highest-yielding shares. Also the income from the portfolio has, overall, kept pace with a theoretical annual inflation rate of 3% for the last fourteen years. Obviously we live in unusual economic times but this inflation protection is certainly an aspiration for a HYP and HYP1 has proved itself on this front so far.

So what are key principles for creating such a portfolio? The starting point is to order the very largest shares (i.e. from the FTSE100) by yield and then to work your way down the list selecting candidates. The questions that need to be asked of each aspirant share are whether it will provide essential sector diversification, with a reliable dividend, and if it is financially and operationally sound. The reason for this is that we want to select for more than just an ability to pay an excellent dividend this year or the next; our companies need to be at least capable of sustaining their payout indefinitely. If a company meets these criteria then it can go on the list and the process repeats until we have 15-20 shares in different sectors.

When looking for contenders the reason for starting with the very largest companies available is simple risk management; these firms will encounter operational and financial problems just as often as any other company but they'll generally be able to ride out difficulties in a division where a smaller company might go to the wall. So the FTSE100 is a good place to start and it's possible to select a wide range of sectors from this index despite its publicised bias towards oil and mining companies (or whatever sector is currently in favour). If necessary there's no harm in seeking out a new sector in the FTSE250 but it's sensible to stick to the very largest constituents of this lower index.

The most significant consideration when choosing companies is to focus on sector diversification (even, and specifically, at the expense of yield). The reason for this is that we're aiming to create a portfolio that can tolerate the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune and the very best way to achieve this is to require businesses to be exposed to different aspects of the economy. This doesn't mean that they won't fall together in a global recession and it doesn't mean that individual shares won't run into trouble (which they surely will). What it does mean is that your portfolio won't be decimated when the oil price halves or the banking sector stumbles into a systemic crisis.

By way of example I began my portfolio with Lloyds back in 2004, added Alliance & Leicester in 2005 (plus some more Lloyds) and then threw caution to the wind in 2007 by bringing in Barclays and Royal Bank of Scotland! What could possibly go wrong with such a group of reliable and high-yielding stocks? I figured that I knew better than the rules and that my portfolio could take the sector risk but I was deluded (and only half-right). When 2008 turned into a bloodbath I lost thousands of pounds selling these shares (willingly or not), put my portfolio back by years and missed out on a lot of of dividends. So sector diversification is absolutely critical and this rule should never be bent in order to select an inappropriate company.

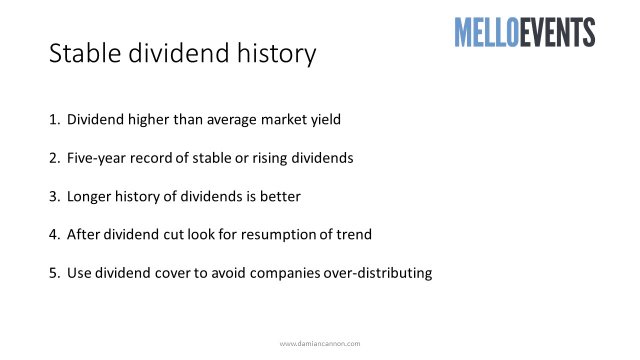

The second most important check is whether a potential holding has a solid, long-term history of paying out rising dividends (which is the case for many FTSE100 shares). If it does then this leads to a couple of conclusions; firstly the directors are probably unwilling to cut the dividend in order to maintain this cherished history; secondly the company likely operates in a relatively conservative manner in order to be able to consistently fund these payouts. Obviously neither of these points is carved in stone but if we're looking to tilt the odds in our favour, which we are, then they're a good starting point.

This doesn't mean that dividend cuts automatically rule out shares (since short-term problems can affect the best of companies) but such a cut needs to be reasonably ancient history (5 years seems fair) and succeeding payouts need to have resumed an upward trend with reasonable coverage. If another cut has occurred then this suggests a company in more serious trouble, perhaps in a structurally declining sector, with a board who haven't got to grip with the issues. Avoid.

A third key point to remember is that these rules aren't intended to allow you to 'switch off' and pick a portfolio in a mechanical manner; on the contrary when selecting shares to hold forever you need to be even more rigorous in your choices. This is where the system widens out to embrace the typical complications that cause a company to cut its dividend (too much debt, operating in a declining market, poor quality earnings) and so to weed out these susceptible firms. Essentially if there is information available, including broker forecasts, that suggests that earnings are likely to materially weaken in the near-term then we should pay attention.

The final key to this strategy, and reducing risk, is that sectors should all be equally weighted. This doesn't mean that you can't buy several companies in the same field, such as BP and Shell, but the total holding in these shares should be equal to that of any other sector. The reason for this restriction is that none of us can predict the future and some of the companies being held will stumble badly at some point in their life - but we don't know which ones until it's too late. So we need to ensure that the impact of these events on the portfolio, and its income, will be the same whatever part of the economy is under the cosh. Where a portfolio is being built up over time then new shares simply need to match the average sector holding at the moment of purchase.

Obviously, though, over time these initial sector weightings will diverge as some shares do better than others. Some investors following this strategy argue that the solution to this is to rebalance the portfolio on a regular basis; overweight sectors get trimmed back while underweight sectors are beefed up on the proceeds. The drawback of doing this is that it adds complexity to the process and forces investors to become aware of share price changes - when one of the attractions of a HYP is that it's a 'lock up and leave' strategy. Perhaps the best thing that can be said about such rebalancing is that while it's not clear that it adds value, above just leaving the portfolio well alone, it potentially won't detract either beyond the cost of the additional trading.

That said the strength of this strategy is that it aims to select a portfolio that can endure and continue to pay an increasing income; implicitly this means that trading, tinkering and timing are not required. In fact such actions are as likely as not to undermine your portfolio since we are not coldly rational machines and our inherent psychological biases often work against us when making decisions (no matter how we rationalise them after the event). There will always be a company that got away, and a share that we wish that we'd avoided, just as there's always a better buying price than the one that we got. But this is all in hindsight; in the round the fluctuations of individual shares are a distraction.

Certainly I've made my fair share of tinkering mistakes that I'm not proud of. While I've made some satisfactory decisions (e.g buying Northern Foods at 100p, selling at 109p and seeing them taken over at 75p or buying Electrocomponents at 288p, selling them at 303p and finding them at 235p a decade later) in reality these were terrible decisions for two good reasons. Firstly these companies have continued to pay dividends and just didn't need to be sold at all. Secondly for each acceptable decision I can find three awful choices to counter them. I sold quality companies, like BT, United Utilities and BP to name just a few, because their yield had temporarily dropped and yet they've all gone on to pay handsome dividends (to say nothing of the price rises I've lost out on). Even worse with some sales I have no idea why I sold a perfectly good share; what on earth was I thinking? Simply put almost all of my tinkering actions have worked out poorly and I doubt that I'm unique!

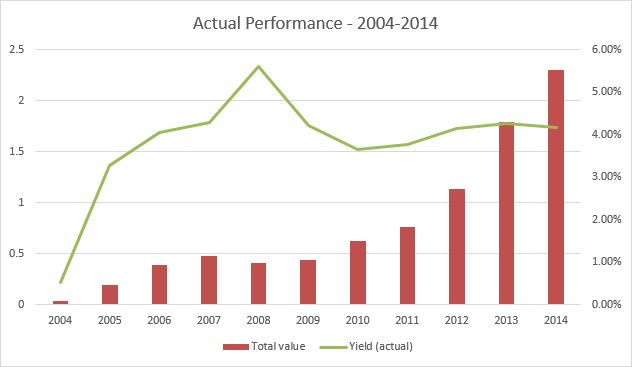

Having just discussed some of my most egregious mistakes, which still pain me, I think that it's worth taking a look at my personal portfolio history. Unlike HYP1 this was, and remains, a HYP under construction. I started just over a decade ago with limited funds and have added to the pot every year; with that in mind it's not surprising that the total value has risen. More usefully, for the purposes of this presentation, the unit value of my portfolio has just slightly more than doubled in its ten years of life; using the Rule of 72 this indicates an average annual return of about 7.2%:

However capital isn't the target of my portfolio. From an income perspective I was quite surprised, when crunching the numbers, to find that the average yield very quickly ramped up to about 4% and has remained at this level ever since. To my mind this is a remarkable result given that we're still recovering from the Global Financial Crisis (where you can see the yield spiking, as share prices fell, and then itself falling sharply as the following year dividends got cancelled) and I broke just about every rule of high-yield investing. If a HYP can survive this double-whammy (and my blundering) then it can probably survive anything!

Conclusion

In summary it's not difficult to create a high-yield portfolio, whether from a lump-sum or bit-by-bit, but it is important to follow the rules. Diversifying by sector is the most critical consideration but within a sector it's sensible to choose companies that have a history of maintaining their dividend and appear well positioned to continue doing this for the foreseeable future. If this means accepting a lower initial yield, compared to other companies in the sector, then this is a compromise worth making.

Perhaps the biggest problem with running a HYP though is that it's rather boring! Once you've got past the excitement of identifying shares that meet the selection criteria, and have pulled the trigger, then there's really very little to do apart from collect the dividends (unless a corporate action occurs). Now there are periods when takeover activity escalates, which is why half of the companies once held by HYP1 are no longer around, but between these feeding frenzies there's often very little going on. If you can cope with this then high-yield investing may be for you.

Disclosure: my investments are substantially invested using the high-yield strategy discussed here and I no longer give in to the temptation to tinker. Mostly.